The Online Revolution: Playing your part as a Virtual Educator

Gilly is a single stem ICM trainee working in South East Scotland. She has an interest in medical education, having recently completed a medical education fellowship as her ICM special skills component.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global healthcare emergency and the NHS is facing an unprecedented crisis. During the first wave in March and April 2020, the immediate priority was understandably on clinical delivery of safe and efficient care for patients presenting with a novel disease process. This led to the suspension of many “non essential, non-covid” services, and included widespread disruption to medical education at all levels, from undergraduate to postgraduate.

With the exponential spread of COVID-19, there was limited time for educators to adapt to the demands of online delivery of medical education, and as a result, many educational programmes were suspended temporarily. With the emergence of the second wave, and a further national lockdown, it is becoming increasingly clear that the disruption that COVID-19 has brought is not short-term, and will result in permanent changes to our ways of working and learning.

With the pressures the healthcare system faces, the need to produce highly trained, competent healthcare staff in a timely manner has never been so pressing. As such, the medical education landscape has been forced to adapt to the fact that the majority of healthcare education will take place without face to face contact for the foreseeable future – the online learning revolution is here. Whilst there has no doubt been disruption to medical education as a result of COVID-19, it is also proving to be a catalyst for the transformation of medical education delivery. On a personal note, as someone who loves medical education, particularly the promotion of technology enhanced learning, increasingly I’m of the opinion that this pandemic is proving to be the shake up that medical education needs.

This blog aims to discuss how existing and novel teaching methods can be adapted to ensure learning opportunities can be maximised, safe care delivered and competency based learning can be achieved for all learners, with some reference to practical, real life examples.

So what are the challenges with the delivery of face-to-face learning at present?

- Reduced learning opportunities for learners

With increasing numbers of positive cases, hospital admissions on the rise and reduced ICU capacity, the elective case-mix within hospitals has been considerably reduced. In addition, the emergency case-mix has also become less diverse. During the first wave, there was a significant drop in hospitalisations with common emergency presentations including out of hospital cardiac arrests and strokes1. Whilst elective work has restarted in some parts of the country, social distancing requirements and precautions around aerosol generating procedures can mean that elective work is slower and more inefficient than previous. This has presented a serious challenge to trainees and other learners in achieving mandatory case numbers required for sign-offs or logbooks.

- Staff shortages

Recent figures published by NHS Digital indicated that COVID-19 resulted in almost 341,000 full time equivalent days of absence in May 2020 alone2. In order to maintain service delivery, staff may be required to fulfil rota gaps and may be diverted away from both educational opportunities and the delivery of teaching to learners to provide care “at the coal face”.

- Social Distancing Requirements

Prior to COVID, it was possible for educators to simultaneously deliver education to hundreds of students in a lecture theatre. With the introduction of social distancing and government guidelines limiting the mixing of households indoors, even small group teaching with several students is likely to be unachievable when delivered using a face-to-face format.

- Limited supply of educational events

Many educational courses and conferences have been cancelled or postponed, meaning that opportunities for staff to partake in activities which promote continuous professional development have been significantly reduced.

- Trainee redeployment

During the first COVID peak, with surge critical care capacity and a requirement to safely care for increasing numbers of patients, many healthcare professionals were redeployed to areas in which they did not normally work, such as critical care. Whilst the extent of redeployment varied enormously across the UK, in some deaneries, the majority (upwards of 50%) of foundation doctors were redeployed to new clinical environments3. This brings with it the obvious challenge of having to rapidly orientate, induct and upskill large numbers of healthcare professionals to safely care for patients, many of whom were critically ill.

- Postponement/changes to exams

Due to restrictions with social distancing, many professional exams have changed or adapted their format, and exam preparation courses and resources have been less readily accessible for trainees.

- Learner Wellbeing

Concerns about the wellbeing of healthcare staff are not unique to COVID – in fact, a government health and social care committee showed that exhaustion levels among staff were at an 11-year high in the months leading up to beginning of the pandemic in March4. But following the onset of Covid-19, rates of anxiety and stress have surged, with a BMA survey revealing that more than 40% of surveyed healthcare professionals were suffering from symptoms of anxiety, stress, burnout or emotional distress5.

Now we’ve identified what the challenges are with face-to-face education delivery are at the moment, how can we adapt our practice as educators to overcome them?

Learner and patient safety is always the top priority when considering how to deliver learning

Learners can both acquire and spread the infection when in clinical areas, or when in contact with others for the delivery of education. Whilst all face-to-face contact risks transmission events there are some learner populations that can be viewed as higher risk. For example, Undergraduates aged 19-24 have amongst the highest rates of infection in the general population, with an infection rate approximately 5 fold higher than the general population rate6.

The first and most important question you must ask yourself in designing and delivering teaching is: Is face to face contact really necessary to achieve the educational outcome I’m after?

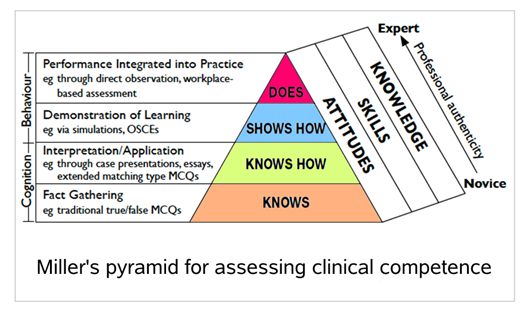

In attempting to answer that question, we can look towards educational theory. Miller’s pyramid is a framework for describing clinical competence in educational settings7. The framework distinguishes knowledge in the lower levels of the framework, and “action” – or applied knowledge in the higher levels.

The most basic level of the pyramid is “Knowing” something. Traditionally, this encompasses lectures, knowledge based small-group teaching and knowledge-recall such as multiple choice questions. Next, you can “know how” to do something – case summaries, exemplar examinations and observation of clinical encounters falls under this remit. Next is “showing how” – which most commonly incorporates some form of simulated component (such as an OSCE, simulation, or clinical skill using a part-task trainer). Finally, a learner can “do” something, which incorporates direct observation in a workplace-based environment.

The most basic three levels of the pyramid do not require direct observation of practice and therefore, in the current climate, with risk to both educator and learner, any learning which hits those first three levels on the pyramid I would argue should and can be most safely be delivered in an online format which minimises direct face-to face contact.

If most teaching can be delivered online, what practical steps can I take for transitioning to the online environment?

Lecture Based Education

These can be delivered either in real-time or can be pre-recorded for convenience. Whilst real-time lectures offer the benefit of interaction with learners, pre-recorded lectures offer the benefit of allowing learners to access material at a time of their choosing, increasing accountability for learners and allowing them to go at their own pace.

The most common platforms for delivering live, in person lectures are Zoom and Microsoft Teams. Microsoft teams has the advantage of security, and most NHS trusts will allow patient identifiable information to be used. This isn’t the case with less secure platforms like zoom. If you’re delivering a real-time lecture, it’s useful to record it using a simple web browser recorder like Screencastify, which will allow you to upload the recording of your lecture so learners can view the recording at a later date.

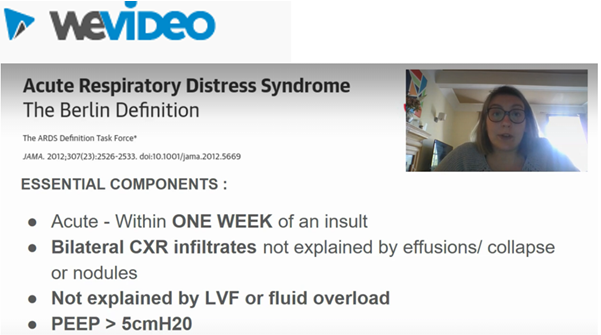

There are many simple video editing tools available free-for use online if you want to pre-record your lectures. A personal favourite of mine is WeVideo as it allows you to record your slides and your face in combination (See image below). The editing software itself is absolutely idiot proof, click and drag, and requires absolutely no technical know-how. The quality of the videos produced is also very good (HD quality).

Multiple Choice Questions/ Quizzes

There are a number of online platforms that allow you to design interactive multiple choice or single best answer questions, that can be used to consolidate and test knowledge based recall. I’m a particular fan of Fyrebox, as seen below, as it allows you to personalise the design of your quizzes, and you can add images such as ECGs, radiology investigation and blood test results, and explanations you our answers. You can also add timers to question sets to allow students to experience a mock-exam format.

Small Group teaching

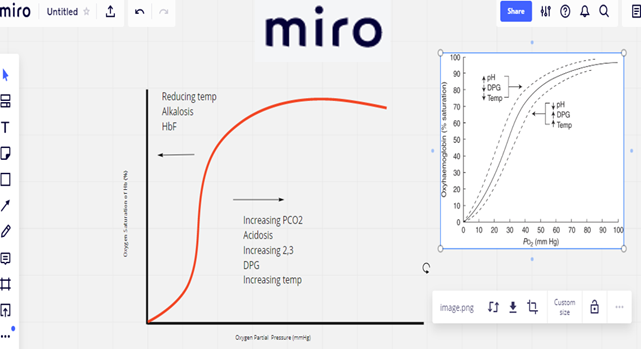

If you would normally deliver your teaching in a small group format, with lots of interactivity, and perhaps a whiteboard, then there are some online options for you too. There’s a free-to-use online learning environment called Miro which acts as an interactive online learning space. It can be used synchronously, where groups of learners can gather to interact together, or asynchronously, where learners can complete tasks before meeting up to discuss, which supports a flipped classroom model of learning. The learning space is flexible and allows you to draw pictures, doodle, insert text and chat in real time with other learners. Below is an example of a trainee drawing an oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve during a real-time tutorial with other learners.

Bedside Teaching

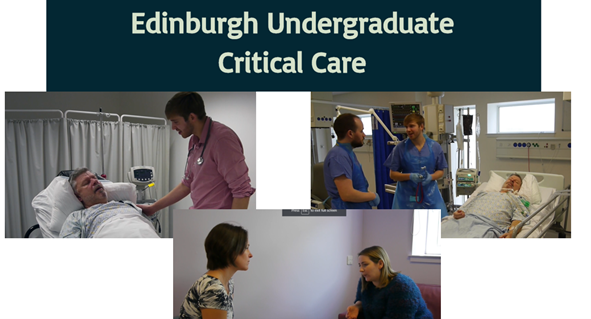

Opportunities for direct patient contact may be limited for learners in some clinical areas, particularly in areas that involve procedures with potential aerosol generation, such as a critical care environment. In order to allow learners to understand the patient journey through the environment, it can be useful to produce resources which demonstrate the expected clinical journey of a patient through a clinical environment. As an example of this, for undergraduate students, we pre-recorded and hosted a number of pre-recorded video resources, with a simulated patient, which demonstrated a typical journey through critical care, illustrating an A-E assessment, a daily review of a critical care environment, and an example family discussion. This ensured that even if students were not able to have direct clinical contact on their attachment, they would have a resource which allowed them to reach the “knows how” stage of Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence.

Simulation

Simulation is an educational technique that recreates real life experience in a controlled way and which provides opportunities for participants to learn, and to apply new knowledge in a safe environment. Despite this, there is increasing evidence that participants don’t actually need to directly take part in a simulation to have effective learning. Systematic reviews of high-fidelity simulation literature identify that debriefing is the most important feature of simulation based medical education8, and this can be delivered via an online platform such as Microsoft teams or Zoom.

As such, we have adapted our simulation materials used in COVID to include a pre-recorded simulation followed by an online structured debrief by an experienced facilitator.

Maintaining Engagement in an Online Learning Environment

Maintaining engagement with learners can be challenging, and online learning environments have the potential to revert to being very didactic quite easily if not thought about and planned. As an educator, there is little more dispiriting than so-called black box teaching (In which participants switch off their cameras leaving you with multiple small black boxes for learners!)

Below are a number of suggested ways in which you can try to maintain engagement with learners in an online environment:

- Ask (but don’t force) learners to turn on their video (avoid black box teaching!). This goes some way to preserving the social nuances and interaction which are so important in social construct of learning

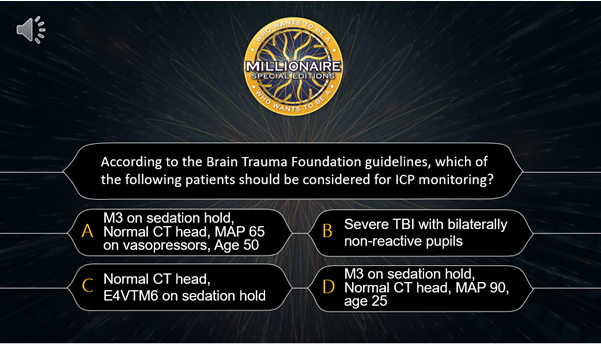

- Make use of breakout spaces/games. Recently, during our departmental teaching, we made use of gameshow learning when we played a game of “Who wants to be a Neuro Critical Care Millionaire” (See Figure 7). We made use of lifelines including Phone A Consultant, Ask the Audience and 50:50

- Interactive polls – There are a number of audience polling platforms which are available free-for-use and allow integration of live audience to lectures of case presentations. Some of the most popular commercially available platforms include Slido, Voxvote and Poll Everywhere

- Encourage questions and discussion via chat functions on Microsoft teams or Zoom.

The online education revolution is here, and will form a significant proportion of modern medical education in the years to come. It is our role as educators to adapt to the changing needs of our healthcare system and learners. With the rapid advancement in the infrastructure supporting online education delivery, the move towards online learning doesn’t have to be scary, and requires very little in the way of technological proficiency. We should aim to work collaboratively, sharing our experiences, ideas and materials as we navigate this new world of online medical education. Our learners are largely digital natives and there is increasing evidence of non-inferiority of online learning to traditional delivery and signals of student preference9.

Having said that, it would be fantastic if everyone could make sure their microphone is muted….

References

- Mafham MM, Spata E, Goldacre R, Gair D, Curnow P, Bray M et al. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet. 2020 Aug 8;396(10248):381-389.

- NHS Sickness Absence Rates May 2020, Provisional Statistics – NHS Digital. [online] NHS Digital. [cited 8 November 2020]

- Redeployment of Foundation Trainees during the Covid-19 pandemic [Internet]. Rcpsych.ac.uk. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020].

- Workforce burnout and resilience in the NHS and social care [Internet]. Committees.parliament.uk. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020].

- Personal impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on doctors’ wellbeing revealed in major BMA survey [Internet]. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020].

- Student neighbourhoods see coronavirus surge [Internet]. 2020 [cited 8 November 2020].

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990 Sep;65(9 Suppl):S63-7.

- Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005 Jan;27(1):10-28.

- Chipps J, Brysiewicz P, Mars M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of videoconference-based tele-education for medical and nursing education. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012 Apr;9(2):78-87.