Max and Keira’s Law – The Bill That Was Pulled Out Of A Bowl

Claire is the Accountable Executive for implementing opt out legislation within NHS Blood and Transplant. She joined NHSBT in 2013 as the Head of Transplant Development. Prior to this role, she was a Policy Lead in the Department of Health for over 15 years.

Max and Keira’s Law came in to force on the 20th May 2020 and brought renewed hope to the thousands of people on the UK transplant waiting list. The legislation introduced ‘opt out’ as the legal basis for organ donation consent in England and is expected to lead to an additional 700 transplants a year. However, the path to getting the new legislation in place was far from smooth.

Cast your mind back to the 4th October 2017. Theresa May was the Prime Minister and about to give her speech to the Conservative Party Conference. Whilst the set fell down behind her and protesters interrupted her, she announced her plan ‘to address the challenge that affects communities in our country…to change the system, shifting the balance of presumption in favour of organ donation’.

Theresa May made the announcement, but the journey to change the organ donation legislation had actually started 3 months earlier, when Geoffrey Robinson’s name was plucked out of a fishbowl (literally – you can watch it here)

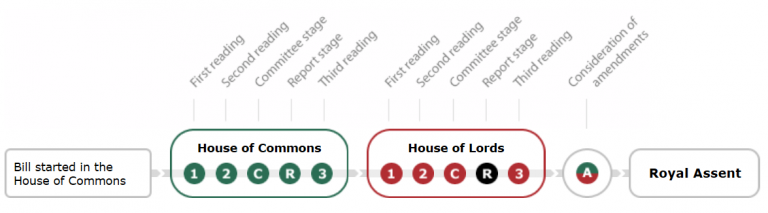

Private Member’s Bills (PMBs) rarely become law. The chance of success are low because it is so hard to get them moving and then so easy to defeat them. There are 13 Bill stages, so 13 opportunities to succeed or fail. Of the 461 MPs who put their name in to the ballot on the 29th June 2017 to introduce a Bill, only 20 names were picked. Of those, only 9 went on to introduce an Act.

If a Bill is not supported then it can be ‘timed out’, by opposing members talking until the allotted time for the Bill has run out so there is no chance for a vote. If they are voted on, then they have to win a majority. A quick trawl through the Hansard records show that PMBs to introduce deemed consent were put forward every few years (e.g. John Marshall in 1997, Nick Palmer in 2000, Tom Watson in 2002, Siobhan McDonagh in 2004 etc). Some made it as far as a Second Reading, but all eventually failed.

So, how did Geoffrey Robinson succeed?

First, even though he was a Labour MP, he had the Conservative Government support. The Prime Minister had placed the introduction of deemed consent as one of her priorities and Geoffrey Robinson had the Bill that could make it happen. This symbiosis outweighed any party politics that might otherwise impede a PMB.

The second reason for the success was that the Tories were not the only ones who supported the Bill. Geoffrey Robinson also gained complete cross-party support. Again, I ask you to cast your mind back a few years and remember the political landscape at the time, so that you can appreciate how remarkable this is. Brexit was tearing the country apart. Leadership challenges were tearing political parties apart. There were accusations of anti-Semitism and the #MeToo movement. Against all of this, organ donation seemed to be the one point on which everyone could agree.

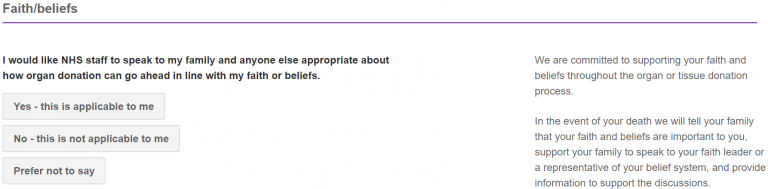

To be fair, I should probably say nearly everyone. Several MPs and Lords raised concerns about the new legislation. Most of these focussed on the role of the family, the autonomy of the individual and faith/ belief considerations. There was a lot of work done to meet with MPs, Lords and representatives from different faiths, family groups, patient groups etc, to listen to their concerns and help alleviate them where possible.

These conversations, together with the feedback from the public consultation, has led to many additional improvements that sit outside the legislation. For example, there is now a faith declaration on the NHS Organ Donor Register to provide clarity and reassurance for those recording a decision. There is a new document setting out, in layman’s terms, the journey through intensive care and the steps taken at every stage to involve family and the point at which donation might be considered. The NHS Organ Donor Register became integrated with the new NHS app. It is doubtful that any of this would if happened if it wasn’t for the new legislation.

The legislation process also brought many other commitments from Ministers, which will benefit the organ donation and transplant process in the future. The then Health Minister Lord O’Shaughnessy’s committed that ‘we will make sure that there are enough highly trained staff to make the most of the changes resulting from this Bill’. Baroness Manzoor committed on behalf of the Government that ‘we will make sure the system is funded as it should be.’ Jackie Doyle-Price, then Under-Secretary for Health, confirmed that ‘there will always be a personal discussion with the family at the bedside, and special consideration will be given to a person’s faith and the views of their loved ones’. Lord Bethell’s committed that they will ‘keep raising awareness’.

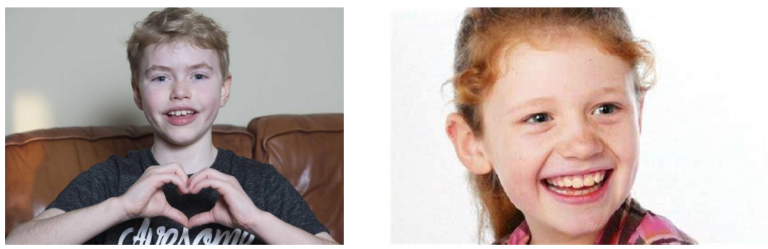

The most influential reason for the Bill’s success was the tireless, selfless efforts by Max Johnson and Joe and Loanna Ball.

Max was a young boy in desperate need of a heart transplant. He and his family had been campaigning for a change in the organ donation system. Keira Ball tragically died in a car accident and her parents agreed to organ donation. Joe and Loanna Ball joined Max in his efforts to introduce deemed consent. Despite everything that was happening at the time, these two brave families helped rally the nation and secured the public’s attention. As a general rule, the Government expects a few hundred responses to one of their public consultations. There were over 17,000 responses to the consultation about opt out – an unprecedented level of response. The new legislation is named Max and Keira’s Law in their honour.

So, on the 15th March 2019 the Queen gave her assent and the Bill became an Act of law. The Act was widely supported and welcomed. The ‘Go-Live’ date was set for the 20th May 2020. A programme of work had begun across the NHS to ensure that the organ donation teams were trained and had resources in place. There were sessions for the intensive care community as well, to ensure that they were aware of the new law and the changes to the discussion with donor families. A public awareness campaign was launched, to ensure that the public knew what to expect. Everything was going to plan.

And then COVID-19 shook the world….

Max and Keira’s Law had progressed so far, but there was still some final regulations to put in place before it could come in to force. Like the rest of the UK, Parliament was in lockdown and had to find a new way to work. Given the urgent need to get clear public health messages about keeping safe during COVID, the legislation awareness campaign was paused.

And yet, the Government remained committed to the legislation proceeding. This may seem counterintuitive, given that this was the height of the pandemic and organ donation and transplant programmes had almost ground to a halt except for super-urgent cases. Intensive care teams were under unprecedented pressure and many Specialist Nurses for Organ Donation had returned to frontline ITU or family support roles, to help in the NHS fight against COVID.

However, if the legislation was not completed, there was a strong likelihood that it would be many months – maybe years – before it could be raised in Parliament again, due to the huge backlog of legislation to get through and that anything relating to COVID or Brexit would inevitably take precedence. The final Parliamentary debates went ahead online and Max and Keira’s Law come in to force on the 20th May as planned.

There were concessions though. Ministers acknowledged the impact of COVID-19 and the extraordinary pressures on the NHS: ‘The Government appreciates that transplants can only proceed where the relevant consent requirements have been met, including the deemed consent requirements where they apply, and it is safe for patients to have a transplant. In reality, this means that this is unlikely that transplants will proceed under deemed consent during the current COVID-19 pandemic because people are distanced and communication between relevant parties is more challenging.’

Thankfully, along with the rest of the NHS, we are seeing the organ donation and transplant programmes recover and deemed consents are now starting to occur. The more we recover, the more opportunity we will have to realise the benefits that Max and Keira’s Law provides.

The work done to introduce and implement Max and Keira’s Law has forged new relationships and deeper understanding between the most unlikely groups of people. It saw the media, political parties, politicians, Commissioners, ethicists, the Government, patient groups, unions, regulators, faith and belief groups, professional organisations, the BMA, clinical teams, BAME communities, and many more, working together, supporting each other, to make improvements that will be felt for years to come. The challenge for us all is to keep the sense of collaboration going so that, together, we can save even more lives through the gift of organ donation.