Update – Management of Stroke and Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Colin is a dual ICM/Anaesthetic Trainee in the North East. His interests include Neuro-ICU, Education and Simulation.

This blog aims to present a brief update on the management of stroke and subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), with particular reference to critical care.

Ischaemic Stroke

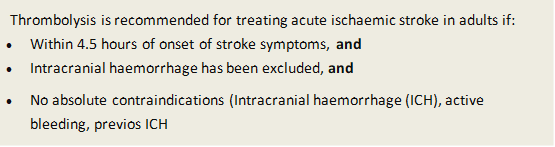

85% of strokes are ischaemic. The classic pharmacological treatment of ischaemic strokes involves thrombolysis (indications below) and/or standard multidisciplinary stroke care including antiplatelets. Blood pressure is not usually actively managed within the first two weeks following ischaemic stroke.

Critical Care involvement in ischaemic strokes was usually limited to those with a low GCS at presentation but newer treatment options are available, increasing critical care input.

MECHANICAL THROMBECTOMY

Mechanical Thrombectomy (MT) aims to remove the causative clot and restore cerebral blood flow using endovascular techniques. Its use in ischaemic stroke is increasing after being formally commissioned in May 2019.

MT can be used post thrombolysis when the clot burden is too large for effective thrombolysis or in those whom thrombolysis may be contraindicated. The most effective results are demonstrated with an event to needle time of less than 6 hours (the quicker the better).

Those most likely to benefit from MT are those with early presentation proximal occlusion of the internal carotid or middle cerebral arteries. Trials of MT on patients who were previously independent reported functional independence at 90 days following stroke increased 19-35% vs. thrombolysis alone (modified Rankin scale).

MT was NOT associated with increased complication rate, death or intracranial haemorrhage.

Provision of mechanical thrombolysis requires a significant resource load and is often only provided in specialist neuro-centres. The increased use of MT may lead to an increased demand for critical care input into urgent transfers.

Post-procedure care locations will be largely organisation dependent but prompt stroke ward care is preferable.

DECOMPRESSIVE CRANIECTOMY

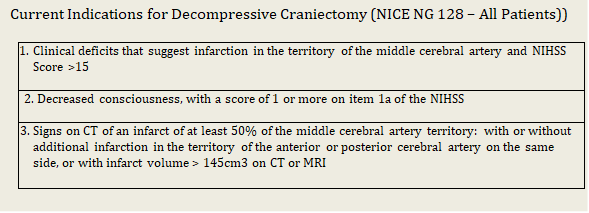

Decompressive craniectomy (DC) is a NICE approved treatment strategy for patients who develop malignant MCA infarction. Untreated, morality approaches 80%. Whilst DC can improve survival, this is often at the expense of significant care-dependent disability.

Originally DC was recommended for those aged 60yrs and under, however NICE NG128 (published May 2019) recommends DC in suitable patients over the age of 60 with a caveat that the pro’s and con’s of this must clearly be communicated between medical staff and families.

It is hoped the evolution of MT may reduce the need for decompressive craniectomy, improving overall outcome in stroke.

Haemorrhagic Stroke

Haemorrhagic stroke accounts for less than 15% of stroke presentations. The major risk factor for haemorrhagic stroke is hypertension.

Critical care involvement in these patients is largely dependent on the site of the haemorrhage, the presence of mass effect and associated complications (hydrocephalus etc.)

Aggressive blood pressure management is recommended by NICE if <6 hours from symptoms onset and SBP >150 mmHg, or >6hours from presentation and SBP >220mmHg, aiming for a target of 130-140mmHg.

Reversal of anticoagulants (if relevant) should occur, alongside neurosurgical discussion for potential clot evacuation.

Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

NICE are due to present updated guidance on SAH in September 2020.

Depending on the quantity and location of blood in the subarachnoid space and the type of aneurysm, treatment options include endovascular coiling or neurosurgical craniotomy and clipping.

Established 7 days a week neuro-interventional radiology services are not universal in the NHS, however the majority of SAH are treated endovascularly. Early securing of the aneurysm can reduce some of the complications of SAH. More peripheral aneurysms may still benefit from surgical clipping as first line.

Critical care management of SAH largely depends on the severity/grade of presentation and the systemic manifestations that the disease causes.

BLOOD PRESSURE CONTROL

There is no universal agreement surrounding BP targets and this should be agreed between local critical care and neurosurgical teams. Suggested targets are:

Aneurysm Unsecured

- SBP 120-160mmHg maintaining cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP))

- Risk of rebleed >160mmHg

Aneurysm Secured

- BP can be titrated up as required to maintain CPP

- Can be increased if concerns of DCI (see below)

RE-BLEEDING

Rebleeding risk is greatest in the first 72 hours post insult; it occurs in up to 10% of patients and is most commonly associated with females, poor grade SAH, larger aneurysms, and those with sentinel bleeds.

OBSTRUCTIVE HYDROCEPHALUS

Occurs in 20-30% of SAH, usually within the first 3 days. It usually requires placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD).

PREVENTION/MANAGEMENT OF DELAYED CEREBRAL ISCHAEMIA (DCI)

Clinical DCI occurs in 30–40% of patients with SAH. DCI can result cerebral infarction and poor neurological outcome. Historically it was thought to be as a direct result of cerebral vasospasm but recent evidence suggests other factors may also be at play. Cerebral vasospasm peaks between 5-14 days after SAH.

Patients with poor grade SAH, large subarachnoid blood load, intraventricular haemorrhage, and smokers are particularly at risk for the development of vasospasm.

Prevention of vasospasm is primarily with regular Nimodipine (60mg, 4 hourly for 21 days). Other strategies used in the past such as triple H therapy (hypertension, haemodilution, hypervolaemia) are no longer reccomended due to a lack of evidence of benefit (aim euvolaemia). Currently only hypertension appears to have a small amount of evidence of benefit in the literature.

There have been multiple trials of drug therapy looking at improving vasospasm when present but non have demonstrated consistent benefit.

Colin is a dual ICM/Anaesthetic Trainee in the North East. His interests include Neuro-ICU, Education and Simulation.

Further Reading

Lawton MT, Vates GE. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):257-266.